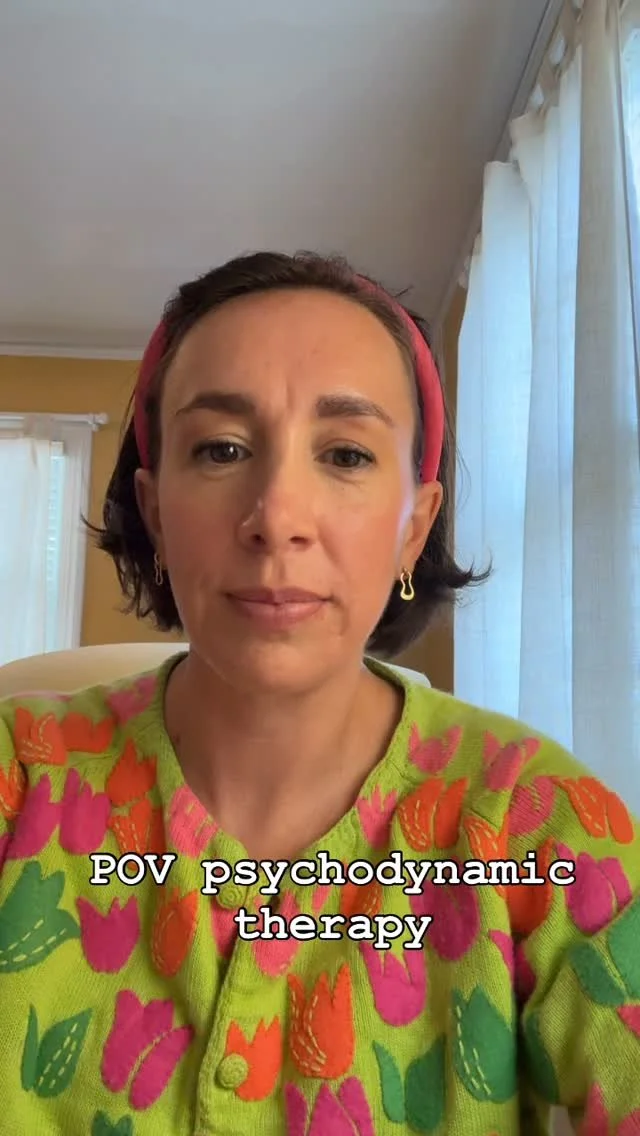

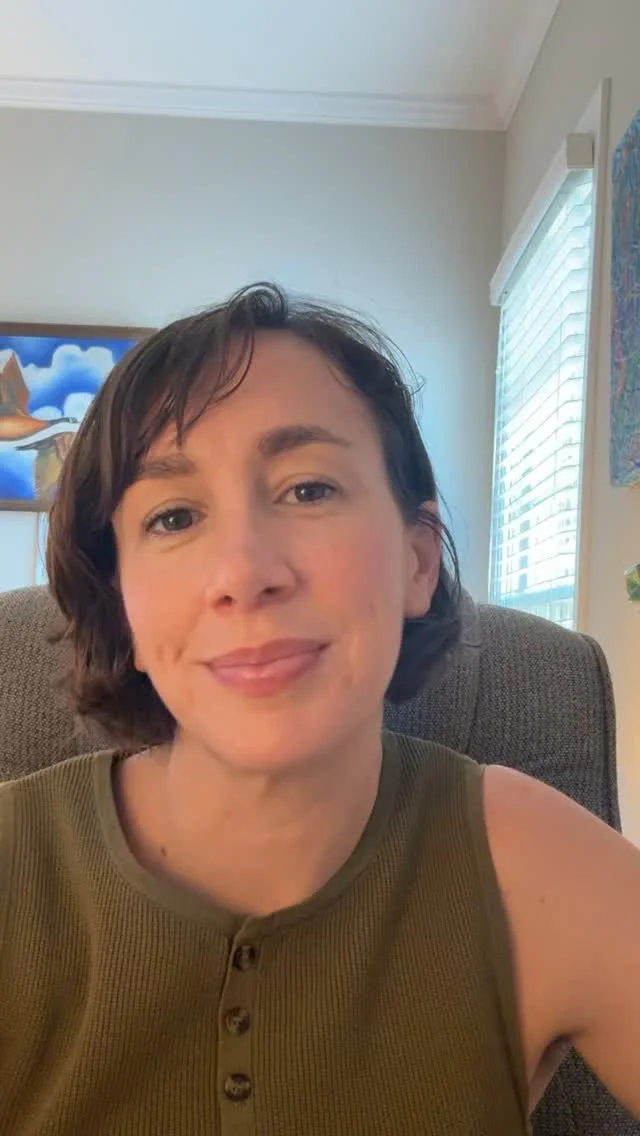

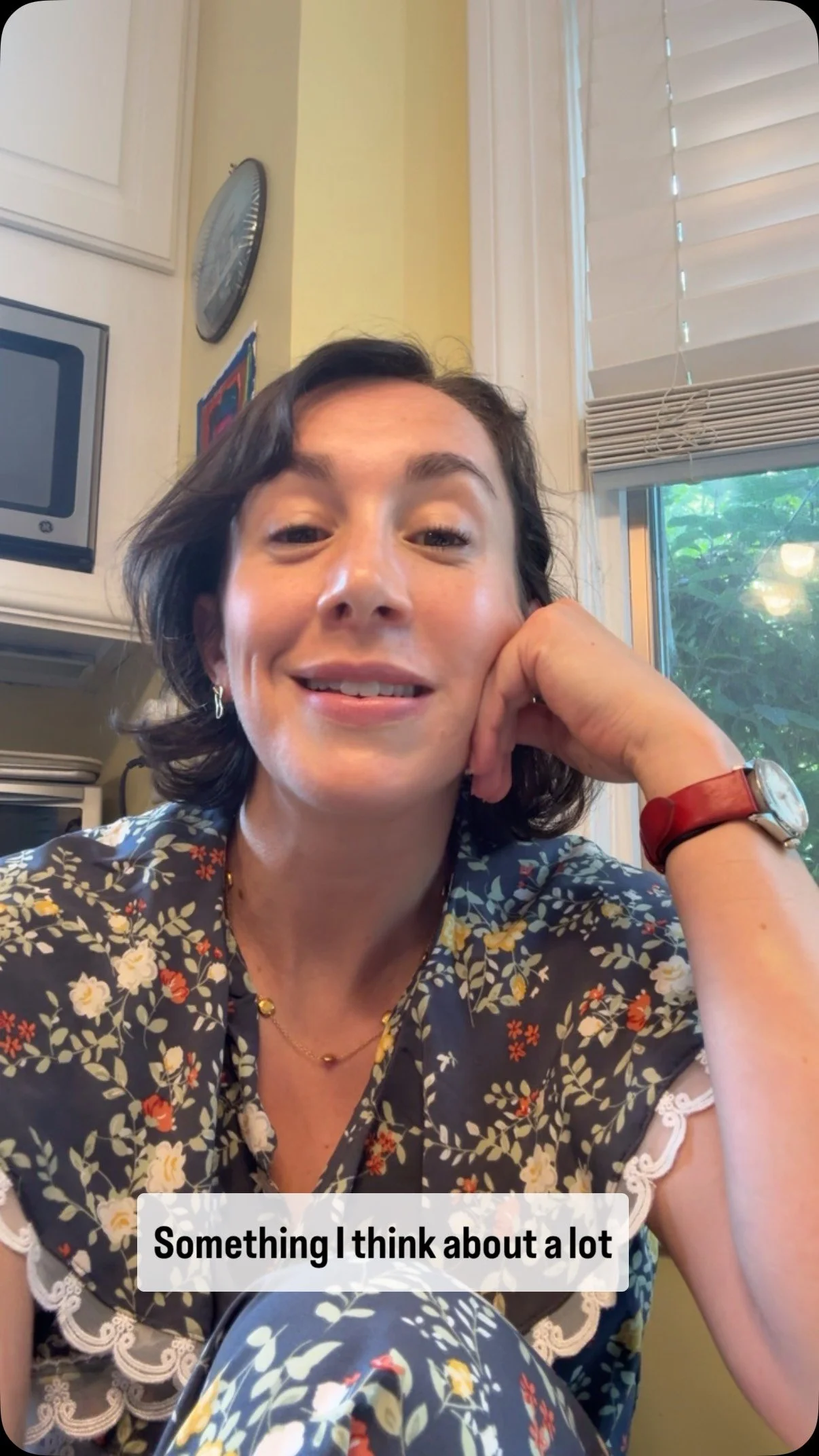

Eva Schildhause, LCSW

Psychodynamic therapy for adults in Fayetteville, NC or online from anywhere in North Carolina or Florida. You deserve relief from anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and the effects of trauma. You deserve to know yourself.

“Emotion, which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it.” - Viktor Frankl

Who I am

I’m a clinical social worker trained in psychodynamic treatment. This means that I work with you in many dimensions, all anchored by the development of a supportive and accepting relationship together. Through a trusting therapeutic relationship, we explore how the past and present are blocking you from inhabiting the fullness of your self. Over time, you can live a richer, more meaningful, resilient life.

Contact Me

Reach out to schedule a free 15-minute consultation to discuss working together or use this link to book a 15-minute consultation call: https://calendly.com/eva-parzivaltherapy/15min